You’d pack differently for a safari than for a trip to the arctic, right? You’d behave differently at a formal banquet than at a picnic, right? For the same reasons an actor approaching a role needs to understand the rules for behavior in the play in which the role appears — and how a specific role is evaluated by the world of the play.

In the world of the play are you well-behaved? Rude? Strong? Weak? Beautiful? Most importantly: How do you survive in the world of the play ? How do you prosper?

The cultural anthropologist Ruth Benedict offers a model for actors to identify the pattern that gives measure to the world of any play. The study of cultural anthropology may seem far afield from the study of acting, but it isn’t really: actors adapt their behavior to the circumstances of a production the way voyagers adapt to a foreign land and learn the local customs in order to survive. Actors, though, go a few steps further than anthropologists: they inhabit the stage world as if born into it, learning an appropriate accent or learning how, circa 1965, to pay respect to a divorced woman who is smoking a cigarette while waiting for a drink.

A world of the play analysis is especially useful for plays that require heightened behavior: Shakespeare, Genet, Ionesco, for example. but also it’s an approach very useful for “realistic” plays. You think Annie Baker’s characters have the same rules in life or onstage as Tennessee Williams’ characters? Think again.

When Lemuel Gulliver—the hero of Jonathan Swift’s 1726 novel Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World —is shipwrecked on the island of Lilliput, he wakes on the Lilliputian beach surrounded by an army of men six inches tall. Gulliver tries to be considerate under the circumstances, but his tiny hosts consider him gross, dangerous, and loud.

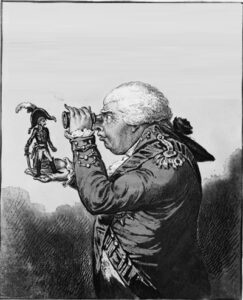

Granted permission to return to England, Gulliver sails from tiny Lilliput and, shipwrecked once again, lands up on the island of Brobdingnag, where the locals are giants twelve times his size. Although Gulliver acts with dignity with the Brobdingnagians, they hold him in their hands and poke at him like he is a doll. Hiding from a monstrous dog by huddling in a forest of grass blades, Gulliver concludes that “. . . nothing is great or little otherwise than by Comparison.”