An episode is something that happens onstage that the audience understands separately from the whole of the play: Romeo reveals himself to Juliet, the Gentleman Caller breaks Laura’s heart, Didi and Gogo wait for Godot.

Using an episodic approach a performer works to make each episode clear to the audience. All elements of a performance: actors, text, music, props, costumes, lights, décor, contribute to an episode as would the parts of a machine. Using an episodic approach, actors in rehearsals and performances create roles in a working ensemble, rather than emphasizing the illusion of a “realistic” character. Working to polish episodes, actors assign headlines that answer the questions What happens? To whom? – while questions of What do I want? and How do I feel? are left deliberately unanswered so as to involve the audience. Contradictions in motivation and action are kept in a dynamic opposition, unresolved by any simple-minded “super-objective.” The effect on stage is simple, direct, moving, and engaging.

Episodic techniques developed in early twentieth century Russia and Germany, based on the study of Shakespeare’s texts and other non-realistic plays. Playing episodes became the international silent film technique and is still the basis of most film work. Onstage an episodic approach is especially useful for Shakespeare, Brecht and Caryl Churchill, but essential for any actor working on realistic plays – Chekhov, Ibsen, and Williams, for example — in which a mass of individual “objectives” can obscure the events and significance of the play.

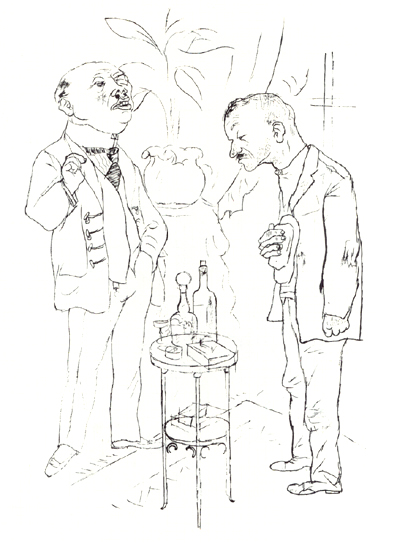

As in George Grosz’s powerful images, an episodic approach to acting has actors mix distortions with the precise details of observed behavior to achieve a style of acting more real than realism.